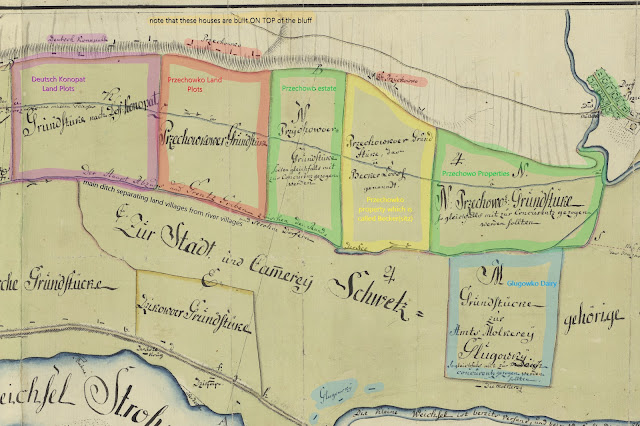

See: https://mla.bethelks.edu/archives/VI_53/Bydgoszcz/Przechowko/PrzechowkoBlatt6BydgoszczArchivesFond1881FileXXXX/IMG_3846.JPG, Mennonite Library and Archives, Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas.

Przechowo – Act of granting the hereditary possesion of a half of the Przechowo Vorwerk (Przechowo manor lands) to 7 previous emphiteutic tenants; 1774, 20th May

Translated by Michał Targowski, Torun, Poland.

Just after the present emphiteutic tenants of the Przechowo Vorwerk belonging to the Schwetz Office, named Andreas Ratzlaff, Abraham Riechert, Hans Ratzlaff, Tobias Ratzlaff, Heinrich Unruh, Jacob Pankratz und Jakob Knels, decided to cede immidiately to His Royal Maiesty a half of that Vorwerk, the contract of which will be over in 1787, inlcuding all dwelling and farm buildings as well as their winter sowing, for reimbursement of the Einkaufs Geldes in amount of 66 Reichsthaler 60 Groschen which once had been paid by them, under condition that in exchange they will be given the other half of that Vorwerck in hereditary and real possession and will be allowed to use this part for the needs of their village, His Royal Majesty graciously decided to accept their proposition from 22 February, hence the following act of Erbverschreibung (ceding the full and hereditary property of the possession) was arranged and concluded:

1. The Westprussian Chamber for War and Domain, up till His Royal Maiesty’s ultimate confirmation, grants and gives one half of the Przechowo Vorwerk, which according to the measurement performed by conductor Matthias has within its borders 4 Huben, 2 Morgen and 297 Ruthen in Chełmno scale, to the previous emphiteutic tenants Andreas Ratzlaff, Abraham Richert, Hans Ratzlaff, Tobias Ratzlaff, Heinrich Unruh, Jacob Pankratz und Jacob Knels, in free, eternal and hereditary possesion in a way that they and their descendents will use these 4 Huben 2 Morgen 297 Ruthen due to their wish, however only for farming, with a right to sell them after aknowleging that fact to the Amt (Office)

2. They cede and give His Royal Maiesty in their own name and in the name of their descendents the other half of the Vorwerk 4 Hufen 2 Morgen 297 Ruthen large, together with all Vorwerk building and their winter sowing, beginning from June this year, and resign willingly and firmly from their former empiteutic rights, and also confirm receiving 66 rthlr 60 gr, which they once paid as a half of the Einkaufgeldes

3. They are obliged to pay yearly from their hereditary 4 huben 2 Morgen 297 Ruthen a half of the previous Canon in amount of 66 Thaler 60 gr to the Świecie Office, a half on St. Martins day and the other half on Candlemess (2nd Febr.) without any reminder, as well as a half of the annual contribution levied upon that Vorwerk in total amount of 6 Thaler, payed in monthly rates.

4. They have to keep the roads and ways within their borders in good condition and plant trees aside them, mantain dykes and damms according to the Damm-Regulations as well as the necessary ditches for conduct of the water and when the need comes to deal with floods; also to clean ditches on Pentecost, St. Johns day and St. Michaelis as well as to serve with their horse and cart (Vorspann) or provide their wagons for military needs and transportation of salt/lumber (salt or lumber, depending on the copy) in exchange for customary reimbursement, give Fourage, serve with deliveries in exchange for payment, work with people and horses when neccessary during construction works levied by the Office or around the mills, as well as to bring an Achtel (1/8) of firewood from Royal Forests for the need of the Office in exchange for the fixed payment 1 rthlr for 1 Achtel; they are also obliged to give Praestanda to the church and school and milling tax and provide necessary people when a wolf hunt is organized.

5. If the above mentioned settlers fully follow this engagement and praestanda are paid, they should be protected by this document in future

This act of granting hereditary possession is signed and sealed by the Westprussian Chamber for War and Domain from one side and abovementioned appliers from the other side

Done in Marienwerder, 20th May 1774

(locum sigilli)

Royal Westprussian Chamber for Wars and Domain

Andreas Ratzlaff (GRanDMA #107095)

Abraham Richert (48255)

Hans Ratzlaff (47733)

Tobias Ratzlaff (42307)

Heinrich Unruh (32124)

Jacob Pankratz (32955)

Jacob Knels (3699)

.jpg)