The native inhabitants of Volhynia included Poles,

Ukrainians (Volhynians, Podolians and Galicians), as well as some White

Russians (Byelorussians) and even some proper (Red) Russians (Ukr: росіяни). In 1795 with the Third Partition of Poland,

local Volhynian noblemen began to offer land to German (Ukr: німці) settlers in the hopes that the

German farmers could convert the swampy forest-land into productive

farmland. Among the German settlers who

accepted such proposals were Mennonites from German Prussia and Brandenburg,

including my Ratzlaff ancestors belonging to the Przechowka and Neumark

congregations. And by the very early

1800s, my Great Great Great Grandfather, Heinrich Ratzlaff, was living in the

village of Karolswalde, which lay about three miles south-southwest of Ostrog.

By the late 18th Century, Prussian Mennonites

began to seek new homes. Their Prussian

homelands, where they had previously enjoyed a measure of autonomy and freedom

from the armed forces, were becoming increasingly a military state with the

rise of Ducal Prussia. Furthermore, the

Mennonites’ ability to purchase new tracts of land had been severely limited by

laws put in place by the Prussian government.

The agrarian Mennonites, theologically committed to non-violence, were

not allowed to purchase additional land without serving in the military or

paying exorbitant taxes in lieu of such service. Additional farmland was a necessity for such

an agricultural based culture.

Therefore, the Mennonites in West Prussia, including those belonging to

the Przechowka Congregation, as well as those in the Neumark area of

Brandenburg, had no choice but to seek new homes outside the boundaries of the

various German states. Many of the

members of Przechowka accepted invitations from the Russian Government to

accept military and tax exemptions and settle far away in South Russia; an area

Russia had recently seized from the Ottoman Empire. Many members of the Neumark congregations,

though, accepted offers from Volhynian noblemen which conversely did not

include such advantageous taxation or military benefits, but which lie much

closer to their homelands in German Prussia and Brandenburg and where the

countryside more closely resembled that of which they were accustomed. Indeed, Volhynia had been part of “civilized”

Europe for centuries whereas the steppe of southeastern Ukraine must have been

the Wild, Wild West. Only very recently

had the area been seized from Ottoman Turkey and wild tribes of nomadic Tatars still

roamed and hunted the vast, untamed plains.

A second wave of foreigners came into Ukraine after 1861

after the emancipation of the Russian serfs.

Previously, serfs in Russia and Ukraine were tied to the land as in a

medieval feudal system. The Russian or

Ukrainian landowners could do as they would with their serfs in return for

keeping the serfs housed, clothed, etc.

After 1861, serfs were freed by the Russian government and were no

longer tied to the land. Serfs were

given the option of buying land from the state.

As a result, many serfs moved off the estates owned by the landholding

elite, leaving a shortage of labor. The

Russian and Ukrainian landowners at this time invited German and other European

farmers onto their estates to work their land.

Mennonites weren’t the only Germans moving into the area;

German Lutherans entered Ukraine in the early 19th century as

well. Lutheranism had been

well-established in Russia since the days of Peter the Great and Lutheranism

was one of only two religions officially accepted by the Russian Government

(Russian Orthodoxy being the other).

German (Prussian) Lutherans moved into Russia in the early 1800s as they

too were offered attractive invitations by the Tsar and saw economic

opportunities in Russian Ukraine. By the

mid 19th Century, the majority of German settlers in Volhynia were

Lutherans. Indeed, in 1862 there were no

fewer than 45 Lutheran German villages in Volhynia. There were also German Baptists in the

Volhynia area. The Lutherans and Baptists were primarily in areas directly

north of Zhytomyr and Novograd-Volyn, as well as in Kovel County. By the

mid-1800s, German Baptists were moving into the area, drawn by religious

persecution in Germany and the availability of land in Ukraine. By the late 1800s, some Lutherans had begun

converting to become Baptists.

Zaslaw and Ostrog counties were populated largely by 6

cultural groups: Ukrainians, Jews, Poles, Russians, Germans and Czechs. Muslims and Gypsies also constituted a very

small percentage of the populace. This information comes from the 1897 census of the Russian Empire. If you're feeling confident in reading Russian, you can find many more details regarding this census

here.

The largest ethnic group was the native Ukrainian population

which formed around 80% of the population and largely adhered to the Ukrainian

Orthodox Church. My German Mennonite

ancestors probably generally confused these folks for Russians, but there were actually very few Russian in the area. The Russians who were in the area were generally despised as foreign overlords perhaps not unlike how the English are viewed in Northern Ireland today.

The next largest ethnic group was the Jewish population. Jewish peoples had lived in this area since

ancient times, but became a larger percentage of the population after the

formation of the Pale of Settlement. The

Jews settled especially in urban areas like Zaslaw, Ostrog or Slavuta, but also

in Cuniv, Belotin, and Pluznoe. Jews

largely engaged in commerce and trade and had considerable economic and

political influence. Although they

suffered as second-class citizens according to Russian laws, they became the

most affluent cultural group in the towns as they owned businesses and

controlled trade. Jews owned print shops

in Zaslaw and Ostrog, as well as warehouses, bakeries, mills and shops across

the area. In time, Jews also became

leaders in the region regarding trade unions, health care facilities and credit

unions. At the time of the Bolshevik

Revolution, Jews largely sided with the communists. As a result, Jews were held in contempt by

most of the other cultural groups and were not to be trusted. The native Ukrainians attempted to gain

independence after the revolution and the Jews who sided with the Bolsheviks

were despised as a result.

The next largest ethnic group was the Poles. Of course, the region in question was under

Polish control for long periods of time, so these Poles were well

established. Dorohosch, Borisov,

Kamenka, Stanislavka, Storonich, Balyary, old and new Husk, small Radohosch and

Siever all had Polish majorities.

Several other towns such as Dertka, Cuniv and Martynie also had large

Polish populations. These Poles tended

to be Catholics or Uniates. Many of them

engaged in agriculture, growing millet or barley, but the soil of the area did

not provide viable farmland. Some also

engaged in horticulture, tending cherry, plum, apple or pear trees. Fresh and dried fruits were taken to be sold

at the markets in Slavuta or Zaslaw.

Since the land was not ideal for farming, however, the majority of Poles

tended to work at various crafts, many of which were based on raw materials

provided by the forest. The Poles made

barrels, wheels, and sledges and produced charcoal from oak wood from the

forest. The village of Kaminka was

inhabited by Poles who produced stonework from the native sandstone. Many others, such as those in Dorohosch,

became expert blacksmiths.

German colonies began to appear in the late 18th

century and the Germans added new skills to the region. Most of the Germans in the Ostrog and Zaslaw

Counties were Mennonite, but elsewhere they were Lutherans or Baptists. The Germans settled in the villages of

Karolswalde, Antonivka, Lesna (Leeleva) and Michailivka, but also lived in the

minority in Pluznoe and Zaslaw. The

Germans had a better understanding of agriculture and did have more success

than other groups at tilling the soil.

The Germans produced crops like potatoes and corn with at least some

level of success. The Germans also

produced dairy products; especially milk which was often-times transported to

Slavuta to be made into butter. Finally,

the Germans also engaged in handicrafts, and excelled in smithing and the

manufacture of agricultural implements.

Germans, unlike the other cultural groups, made the schooling of their

children mandatory from an early date, regardless of gender or land-holding

status.

Czech colonists became established by the second half of the

19th century, and largely populated the villages of Antonivka and

Jadwanin. Czechs also lived in the

minority in Lesna, Michailivka and Stanislavka, Karlswald, Martynie, Dorohosch

and Bilotyn. Czechs found the

availability of inexpensive land in Volhynia appealing, especially after

worsening relations with their ethnic German overlords in Austria-Hungary. The Czechs and other Slavic groups in Austria

were a limited minority group. The

limitations placed upon them by the Austrian (German) rulers helped spark WWI

by the second decade of the 20th Century. Czechs largely engaged in agriculture, animal

husbandry and forest industries. Other

Czechs excelled at weaving. Finally,

Czechs were known to erect the best water and steam mills.

A special note should be made of the Muslim Tatars who lived

in the area in Yuvkitski as well as on the northern outskirts of Ostrog. These Muslims were descended from the Mongol

hordes which invaded the area in the 1240s and were overlords of medieval

Russia, Chernigov and Kiev. Muslims

prevailed in southern areas and continued to raid into European Russia and

Ukraine into the 16th century from their capitals in Sarai on the

Volga and the Crimea. Mennonites in the

Molotschna Colony in South Russia also lived side by side with Mongol

descendants; the feared Nogai tribesmen who occasionally raided Mennonite herds

on the south Ukrainian steppes. The

Volhynian Tatars were probably more tame, however, as the topography of the

land required the Tatars to give up their nomadic ways, unlike their south

Ukrainian brethren.

The final significant ethnic group in the area was the

Russians. The Russians gained control of

Volhynia/Ukraine via the partitions of Poland and began to increase in number

throughout the 19th century.

Russians established the seat of Russian Orthodoxy for the area in

Zaslaw. Zaslaw also housed offices for

government officials and barracks for a military garrison, both of which were

populated chiefly by Russians. Early in

the 20th Century, a military garrison was also built in Cunev. Members of the government administration, as

well as of the police force, were largely Russians in the 19th

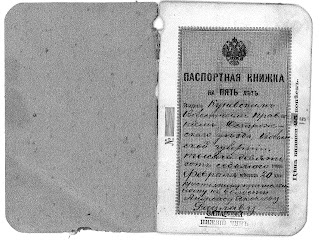

Century. From the turn of the 20th

Century, all official documentation in Ukraine was done in the Russian

language. Russians lived chiefly in the

towns where administration was housed, Zaslaw, Ostrog and Slavuta, although

smaller offices in towns like Pluznoe or Cuniv meant these smaller towns also

held a small Russian populace. Russian

presence in smaller villages was non-existent.

There were, however, a very small number of Russian “Old Believers”

living in the Ostrog and Kuniv forests.

Towns and villages each had their own houses of

worship. Those towns with multiple ethnic

groups might have had Orthodox as well as Catholic churches. Towns with larger Jewish populations would,

of course, have a synagogue. Oftentimes,

cemetaries were segregated by religion or the different religions would

maintain separate cemetaries altogether.

In the 19th Century, all these different groups

of nationalities contributed to Russia’s stunted economic, social and

industrial growth. In the 18th

Century, as Germans or Czechs were invited to move into the Russian Empire,

they were allowed to keep their own languages, conduct their own schools, and

even administer their own villages. Some

were exempt from military service and all seemed to become more affluent than

the native Ukrainians and the Russian overlords. As unrest grew in Russia during the 19th

Century, the Russian government became obligated to remove some of the rights

enjoyed by these national groups in an attempt to unify the populace. For instance, having Germans living across

the countryside, administering their own schools and villages, speaking their

own language and owing little to the State except taxes, did nothing to

contribute to a unified society and only stirred unrest. As the Russian government saw what damage was

being done, it began to remove these special privileges and rights from these

minority groups. For instance, Germans

were no longer allowed to administer their own villages and Russian teachers

were installed to teach the children, and to carry out the education in the

Russian language. This process was

called Russification and was an important part of Russia’s domestic policy by

the second half of the 19th Century.

Russification turned out to be too little too late,

however. In addition to other

shortcomings, Russification only served to further disillusion the populace and

revolutionary ferver by the turn of the century was ripe. The Russian Revolution unseated the Tsar and

by the 1920s, the minority groups were suffering heavily under the new

Bolshevik regime. In Ukraine, a large

percentage of the so-called Kulaks, the wealthy middle class, were Germans,

Poles and Czechs. Many of these peoples

fled over the borders into Poland when they had their chances after the war

with Poland in 1921.

In the 19th Century, there were a couple dozen

villages in the area, in addition to the larger towns of Ostrog and

Zaslaw. Many of these villages were

inhabited strictly by one cultural group or another, each group establishing

its own church and cemeteries and clinging to its own native language and

customs. Since this was a border area,

researching these villages today can be confusing as many different spellings

for the towns and villages exist. For

instance, the village that in today’s Ukraine is spelled Pluznoe (Плу́жне), was

spelled Pluzhnoe (Плужное) under Russia/Soviet rule, Płużne under Polish rule

and was known as Plushnoje by the nearby Germans. Further, it would have had an altogether

different name in the Jewish language of Yiddish. Many difficulties arise in keeping all the

transliterations straight.