In 19th

Century Russia, citizens were recorded for a variety of purposes. Certifying identity provided the government with

citizenship records providing data to tabulate taxes, to provide lists for

military conscription, to record social estate status, to record land

ownership, or to preserve hereditary information. Citizenship records were kept in two ways: 1)

metrical books recorded by the clergy, and 2) internal passports purchased by

the citizen from the local police.

Metrical Books (Metrika) first appeared under Peter the

Great as a tool for cataloging the population of the Russian Empire. Beginning in the early 1700s, the government

required that clergy keep the metrical books, starting with the Russian

Orthodox Christians. Gradually, the

requirement spread to other religions in the Empire including Protestant

Christian, Roman Catholic, Islam and Judaism.

However, Buddhists in the east and the recognized pagans in European

Russia, escaped registration in metrical books entirely. The books created the fundamental register of

identity in the Empire and served as the basis for civil status. Regardless of social station or religion,

citizens were required to report to clergy to have recorded births, marriages

and deaths. The records created the

official documentation needed to identify birthdates, social and civil rights

of an individual, and provided lists from which were drawn tax registers and

military draft notices.

The government

issued instructions to clergy that metrical books were serious records and

their maintenance was of utmost importance.

Yearly, parish clergy submitted their metrical records to local

government authorities. This inclusion

of the clergy into such vital record-keeping shows that the Empire’s government

was indeed moored to religious foundations.

However, suspicions arose from time to time that certain clergy were not

fastidious enough in their record keeping which the government may have

evaluated as sabotage or treason.

Catholics, Jews and Muslims were from time to time put down as being

poor record keepers. Obviously there

were many problems with this system; Lutherans wanted to keep their records in

German, and Tatar Muslims in their native languages, etc. What was to be done if a citizen converted to

a different religion or confessed to no religion at all? What if a new religion was formed? Metrical books lasted until the Tsarist

government was put down by the Bolsheviks and the process was never taken over

by civic authorities.

-“Between

Particularism and Universalism: Metrical Books and Civil Status in the Russian

Empire, 1800-1914”, Paul W. Werth, UNLV.

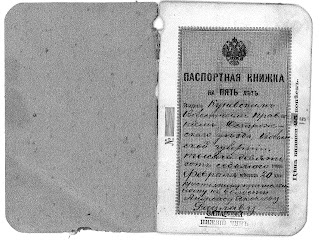

Passports (pasportnaya kniga): internal passports

had been in place in Russia since the early 18th Century as Peter

the Great instituted their use as a way to certify a person’s legal place of

residence. Internal passports,

identifying the bearer by occupation, residence, and estate, helped regulate

travel and prevented evasion of taxes and military conscription. Passports held by those belonging to lower

social orders were registered by the local administrative institutions or rural

societies and bound the holder to his residence and form of employment; the

passport illustrated that a person belonged in a particular place and to a

particular vocation. By the late 19th

Century, members of lower social orders received passports that were valid for

five years, after which time the bearer was required to renew the document. Each social estate had its own local

administrative body. All members of

lower social estates were held responsible for the collective burden of taxes

levied on their social estate. The

administrative body certified that an individual had paid his taxes and was

eligible for a passport. Yearly fees were

also paid on the passport as a sort of tax on free movement. Local administrative bodies could also place

limitations on a person’s free travel rights.

Literate passport holders, usually members of higher estates, signed

their document while the lower orders made their mark or recorded their

physical description. Members of higher

estates received passports which were less restrictive.

-Documenting

Individual Identity, Jane

Caplan and John Torpey ed, Princeton 2001.

Chapter 4, pp 67-80.

Andreas Ratzlaff’s

passport is an example of a pasportnaya

kniga.