After a very poor night sleep, I finally got up and headed

out to try to watch the sunrise on the Vistula.

I had been up and down all night.

My head had been full of thoughts about seeing Przechowka and

Tragheimerweide that day. Did I have all

my notes? What were the ancestors’ names

again? Was Gross Lunau on the south side

of the river by Kulm or north up by Montau?

Or was that Gross Lubin? What

would it be like to actually see Przechowka?

And, wait a minute, I need a photo of the sunrise on the Vistula and

right here, in Toruń (Thorn), is the only spot where the river runs [roughly]

east-west. So that photo of the sunrise

was a one-time shot and that shot was right now. Sunrise was about 4:10 am so I popped up

quickly and was off.

|

| Sunrise along the Vistula |

And it turns out that the river was just off due east-west,

pointing just a bit north, so there wasn’t a good sunrise picture at all. I wandered around the old city of Toruń,

walking 2 or 3 miles before breakfast – all on 2 or 3 hours of sleep. My big day, the momentous occasion when I’d

finally see Przechowka, was in danger of being ruined by sleepiness. Most cafes weren’t open yet (6am) but I

finally found a shop where I could get a cup of coffee and then headed back to

the hotel for breakfast.

Back aboard the bus and I had my own row for the day. I felt a little alone but that was probably

just the lack of sleep talking. Our tour

guide announced the schedule for the day: Chełmno (Kulm), Schönsee,

Montau, Tragheimerweide, and on to Gdańsk (Danzig). Hmmm, will we not even be stopping at

Przechowka at all?

Driving north from Toruń, the first stop of the day was at Kokocko

(Kokotzko in German), several miles southwest along the river from Chełmno. I wasn’t too concerned with this village

since I honestly wasn’t even familiar with the name. And then we began approaching Chełmno from

the south-southwest. One or two of the

towers of the city (probably the rathaus or the cathedral) could be seen

from some distance away and I realized that the town is built upon a hill. As we approached it, we dropped down into the

Vistula floodplain and this was the first real indication of the depth of the

Vistula floodplain in this area.

The Vistula flows in a northerly direction and has changed

its course many times over the centuries.

Over the course of time, a valley has been carved out – somewhat wider

than the river. At the edges of this

valley is a steep climb to the high ground above. In this area, these bluffs were pretty thick

with trees. On the south side of the

Vistula, east of Chełmno, this valley was very

wide. On the north side, between Świecie

(Schwetz) and Grudziądz (Graudenz), it became increasingly narrow west to

east. The bus had to pull quite hard to

go up the incline to climb out of the floodplain.

|

| Church of the Assumption, Chełmno |

|

| Rathaus at Chełmno |

We arrived at Chełmno and immediately headed to see the

military academy which had been bought and paid for by Mennonite taxes in the

18th Century. But honestly

this building didn’t really interest me that much. Yes, Mennonites paid for it, but neither

designed nor lived in it. I was honestly

more concerned with the Renaissance rathaus (city building) of Chełmno and

the huge cathedral (both of which we also stopped to look at). The rathaus is surrounded by a large

square and there was a farmer’s market of sorts going on. Did my ancestors come to this very square to

sell their goods centuries ago? As we

walked across the market, I imagined such a scene. Ratzlaff or Wedel or Voth or Buller or Koehn ancestors

hauling bales of linen or baskets of vegetables or even livestock to sell here

at this very market.

We re-boarded the bus and headed toward the road, route 91,

that I knew would take us east around town to the bridge over the Vistula

toward Świecie. About this time the

guide pointed out the red and white striped chimneys rising on the north bank

of the river just west of Świecie. He

said this was the location of Przechowka, so that was my first look. I could see the bridge in the distance and

imagined, as I looked down from the right side of the bus, that the village of

Ostrower Kämpe

(Ehrenthal) would have stood right down there somewhere, along the banks of the

river, east of the Chełmno road. As we

crossed the bridge the village of Głogówko (Glugowka) was on the opposite side

of the road so I strained to look. The

river was quite wide here – almost exactly 1500 feet wide. The road hardly fell or climbed as we

approached or left the bridge, indicating that the banks of the river didn’t go

uphill much at all.

|

| The village of Ostrower Kämpe would have been right down there |

We turned left (west) on Bydgoska Road and the Mondi factory

with the big chimneys was coming up quickly on our right. Articulated trucks (not 18-wheelers like we

know in USA but articulated trucks nevertheless) loaded with logs plied the busy

road. The Mondi factory produces

cardboard for packaging, as well as paper bags, and is one of the largest

producers of such products in Europe. It

completes huge numbers of cardboard containers for local use as well as for

export to Germany and western Europe.

Established in 1961, the plant has been responsible for massive amounts

of pollution to the Vistula and Wda Rivers.

Only in very recent years has the plant moved to clean up its act in

regards to pollution. Up ahead a little

bit I could see a couple huge piles of what turned out to be ground up logs –

apparently fuel to be turned into cardboard.

|

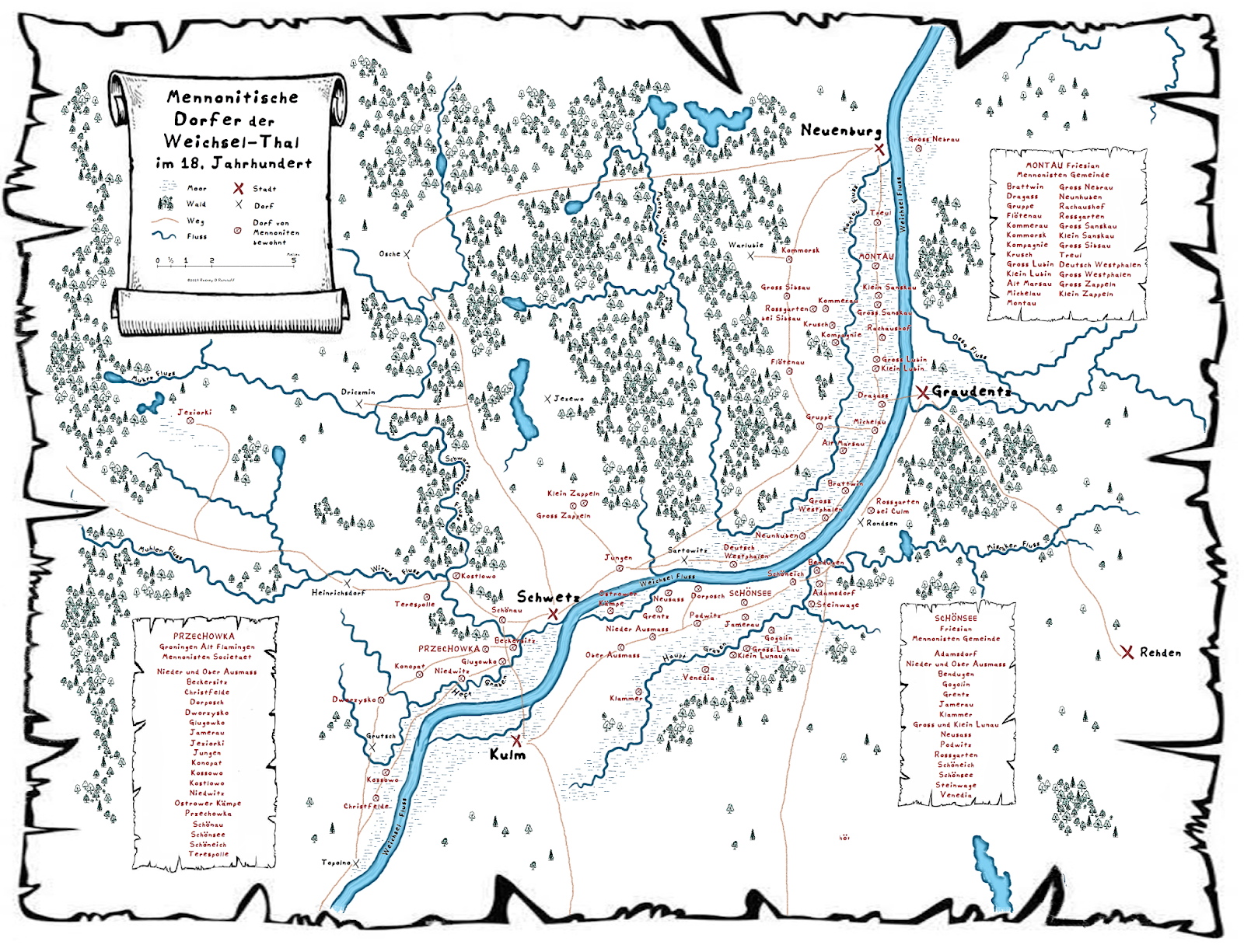

| Villages of the Montau, Przechowka, and Schönsee Gemeinden |

The bus pulled off the road to the south in a small turn-in

and the guide announced that this was as close to Przechowka as we’d be able to

get. We were directly opposite the

factory and Bydgoska Road behind us was actually quite busy. He allowed us a minute or two and then we

went west another mile or so and stopped beside the sign for the village of Wielki

Konopat (Gross Konopat; Deutsch Konopat) for photos. I was the second one off the bus and got a

decent photo of the sign. I then had

just a couple moments to stand and reflect… this was the first glimpse on the

trip of where the ancestors actually walked.

Ratzlaffs and Wedels, Bullers, and Koehns. Voths, Nachtigals and Sparlings. Old Hein Richert, Dina Thoms (my 8th Great Grandmother), and Steffen

Funck all would have been here. I have

proof that Hans Ratzlaff, the son of the first Mennonite Ratzlaff (my 8th Great Grandfather), actually

lived right here in the 1660s! I was now

standing here too. But it was

anti-climactic because I was steady-sleepy, the trucks on the road were

thundering by, and the others from the tour were busy visiting with one

another. I couldn’t really emotionally process

where I was but after took a couple quick photos I put my camera away. Rather, I wanted to actually experience the

moment rather than concentrating on getting “just the right pic”.

|

| Przechowka |

|

| Przechowka |

I walked a couple steps off the side of the road into a

small clear area, knelt down, and put my hands on the ground. I dug my fingers into the earth. I concentrated just for a moment on the

sounds of the birds and the smells in the air.

When my ancestors lived here, they didn’t have the trucks passing by on

the paved highway. They didn’t have the

factory nor tour buses full of people nor mobile phones with cameras. They lived their lives, right here, and heard

these very birds and smelled these very trees.

And most of them based their whole lives on what they grew out of this

very soil. Photos were never going to be

able to convey this so I wanted to be careful to actually stop and concentrate

on the moment so I’d always have the memory.

|

| Road sign for Gross Konopat (Wielki Konopat) |

We re-boarded the bus and headed back across the river (past

Glugowka, past Ostrower Kämpe) and this time turned towards the east. Our guides talked about the Nickel stone

which we’d be on our way to see in Szynych (Schöneich). This was a village of the Schönsee

gemeinde; a gemeinde founded by the mid-17th

Century. The Gronigen Old Flemish from

Przechowka also had a meetinghouse somewhere near the village. Villages in the Schönsee community included some

just south of Grudziądz, all the way around to the eastern edges of Chełmno.

We drove along the very road that takes one through Górne and

Dolne Wymiary (Ober and Nieder Ausmass), and Podwiesk (Podwitz) and continued

on to Szynych (Schöneich) where the Nickelstein stands on the east side of the

village Catholic church. The Nickelstein

is the only monument the Mennonites ever left in Poland but it was erected

fairly late in the day so to speak (that is, it wasn’t erected until a great

many of the Mennonites had moved on to Russian Ukraine) and therefore it was

hard for me to relate to. Also, the

story of the stone, what it stands for now and what it was supposed to stand

for then, have become a little mired in politics or money, so I’ll just leave it

at that.

|

| Schönsee cemetery |

Afterwards, we double-backed to

the Sosnówka (Schönsee) cemetery which is on the north side of the road just

east of the street that one would take toward Brankówka (Jamerau). Finally, we looped around to the village of Wielkie

Łunawy (Gross Lunau). Here the village

mayor had arranged for us a short reception at Chata Marcina from where we

walked west to the old Mennonite cemetery.

The mayor himself proudly maintains this cemetery and was happy to tell

us so. He was beaming with pride – I

could almost see the rays of light coming out of his face – and he was so happy

to have us as his guests. His wife

personally took our orders for tea or coffee and he had little pastries for

everyone. By American standards he

clearly was not a rich man but he was generously providing everything he

could. As our bus pulled away and the

visit was over, he, his wife, and his daughter, all almost literally waved

their arms off in farewell.

|

| Field near Gross Lunau |

From Wielkie Łunawy, we drove east through the ex-Mennonite

village of Gogolin and pulled up out of the floodplain, heading into Grudziądz

on the S5 from the south for lunch at the Alfa Centrum shopping mall. I opted for KFC – I know – but my American

stomach needed something deep-fried by that time. After lunch, we crossed to the west side of

the Vistula on route 16 and turned north towards the village of Dragacz (Dragass)

(immediately south from here is the village of Michale (Michelau where

Mennonites lived from at least the 1660s).

Across the river were the bastions of Grudziądz, the towers and walls of

which come right down to the river’s edge.

These bastions would have been fully visible to Mennonites villagers in

Dragass, Michelau, Gross and Klein Lubin.

|

| The bastions of Grudziądz from Dragacz |

We headed north through Mennonite country stopping to look over the dike

which ran parallel to the river between the road (route 207) and the Vistula

(this dike may very well have been constructed by Mennonite villagers of the

Montau Gemeinde in the 16th or 17th Century). We stopped at the southern edges of Montau (Mątawy)

to look at an old, dilapidated Mennonite house which is, again, still occupied

by a family of Poles, and continued on to the Montau Church. The church, which had been erected in the

late 19th century, is a red brick building on the east side of the

road. Notably, it has stained-glass

windows signed by the man who endowed them to the church, Johan Bartel.

We were greeted by the residing Catholic priest who was overjoyed to

host us.

|

| The Montau Mennonite Church |

Montau was another of the valley Frisian gemeinden. It could have been established as early as

the mid-16th Century and congregants lived in a long swath of

villages from Nowe all the way around to Sweicie. Originally it was aligned with the Flemish

but in time switched over to Die Andere Kant (the other side, meaning,

the faction opposite to that which one belonged). There seems to have been a bit of intermixing

among both the Montau and Schönsee communities with Przechowka.

Perhaps more noticeable here than with other Mennonite

locations, the villages of the Montau Gemeinde are really stretched out

along the valley from Tryl (Treul) in the north all around to Wielkie Stwolno

(Deutsch Westphalen) in the south. When

we Americans picture old, European villages of farmers, we tend to picture them

the way they were in Russia – that is, houses packed next door to one another

along a main village road with fields stretching out behind each yard. This is the way the villages were in Ukraine

(Russia) but not in Polish Prussia. And

the villages of the Montau Gemeinde illustrate this perfectly.

Mennonite houses in Polish Prussia sat, perhaps fairly

centrally, on their field-land. In the

Mennonite village of Jeziorki (Jeziorken or Kleinsee), the farmers each had 1 Hufe

of farmland (about 40 acres) so here in the Montau area it could have been

similar. Thus, if each farmer’s plot was

about 40 acres (let’s say 1,320 feet long by 330 feet wide, and each house is in

the middle of the plot, then the houses were about 400 yards from one another –

and that’s about the way they were – 300-400 yards apart from one another. They didn’t live clustered in a village the

way they did in Russian Ukraine.

And since the houses were spread out in this way, you never

get a sense of a “village space” the way you might think. On a map, all the houses just string out

along a road and there’s no real indication of where one village ends and the

next village starts. Local administrators,

somewhat arbitrarily, just drew lines around a collection of houses and called

it a village. Thus, very apparent with

the Montau Gemeinde, when you look at an old map it’s all almost one

long continuous string of houses from Deutsch Westphalen all the way to Treul,

but administratively it’s divided into many small villages, each including a

small number of villages. All the

Mennonite villages in Poland were laid out like this.

|

| Tree-lined road at Montauerweide |

From here, we headed north through Tryl, on to Nowe

(Neuenburg), and crossed the Vistula on routes 91 and then 90 towards

Kwidzyn. After Kwidzyn (Marienwerder),

we headed north and finally ended up at Mątowskie Pastwiska

(Montauerweide). After a short

look-around, we went a little farther north to the Mennonite cemetery at

Barcice – at last, Tragheimerweide and the home of my Penners and Lohrentzes,

Dirksens and Janzens. We stopped at the

more southerly of the two cemeteries in the Tragheimerweide vicinity, just east

of route 602. This is the cemetery that,

on the 1909 map is marked Tragheimerweide and not Schweingrube. I marveled at the amazingly tall pine trees

growing in the large forest here.

|

| Location of Tragheimerweide cemetery |

|

| Forest near Tragheimerweide |

|

| Tragheimerweide |

|

| Tragheimerweide |

|

| Tragheimerweide |

|

| Tragheimerweide |

|

| Tragheimerweide |

|

| Tragheimerweide |

|

| Tragheimerweide |

Tragheimerweide was the last of the 14 Mennonite Gemeinden

to be established in Poland. Around 1709

a flood had devastated the Ducal Prussian area surrounding the Neman (Memel)

River lowlands in present-day Lithuania.

The Duke therefore invited Mennonite settlers from the Vistula valley to

come to his realm. Members of the Montau

Gemeinde accepted the offer and moved to Ducal Prussia. Quickly, however, there was a falling-out

since the Mennonites refused to participate in the military, and the Duke

expelled all the Mennonites. Upon return

to the Vistula valley in 1724 and 1737, these Mennonites founded

Tragheimerweide, in Royal Prussian land just on the east banks of the

Vistula.

Heading north into Sztum (Stuhm),

we stopped for a bathroom and ice cream break at a ubiquitous Orlen station and

then continued north on route S5. We

passed for the first time Marienburg Castle at Malbork (Marienburg), and

continued on through the Gross Werder to Nowy Dwór Gdański (Tiegenhof). From there we turned west onto the S7 which

would take us into Gdańsk, and at last to our hotel, the Admiral. Dinner that night was at the Admiral Hotel

and later I did have just a little daylight left to walk around the old city

and see the buildings.