Initially when the Andreas Ratzlaff family settled in Kansas, they rented a farm in the southeast corner of Section 24, Menno Township, Marion County, Kansas. The lived on this farm until 1914. During this period of time, the Ratzlaff children attended Steinbach School which was located at the extreme northeast corner of Section 23. After 1914, the family moved one mile south, and lived on a farm at the southeast corner of Section 25. At this time, the children had to move schools and attend the Antioch School, located at the northwest corner of Section 36. My Grandfather, Albert Ratzlaff, was just a little guy when attending Steinbach, but went to Antioch for most of his childhood years, through 8th Grade. I remember driving down the road with Grandpa when I was young, past the site of the school where there was still a hedgerow that had bordered the schoolyard. I remember how Grandpa pointed out that many a baseball was lost in that hedgerow when he was a schoolboy. My dad, Norman Ratzlaff, also attended the Antioch School in the early 1940s for elementary school. When they were grown and struck out on their own, three of the Ratzlaff boys acquired land along the road running between Sections 24 and 25 that would later become a blacktop. Albert's farm was located in the northeast quarter of Section 25, Jacob's in the southeast quarter of Section 23, and Abraham in the southeast quarter of Section 22.

Monday, January 21, 2013

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

Social Divisions in Imperial Russia

Russian society was

strictly divided into social classes or estates (sosloviia, cословия), separating one social group from another. Like other European societies, this soslovie (сословие) system had existed

from medieval times. As in other

European countries in the 19th Century, four basic sosloviia existed: 1) nobility, 2) clergy,

3) urban commoners, and 4) rural peasants.

The hierarchical system began at the top with the tsar and continued

down to the lowest peasant. The system

had religious foundations; the tsar was given his position by god and the

hierarchy was seen as established by god as well. People felt secure knowing they had a place

within society. Raznochinet (разночинца) was the term given to those who fell between the

nobility/clergy and the peasantry (the growing middle class). Nobility consisted of hereditary and personal

nobility. Divisions existed in the

clerical class depending upon the clergyman’s specific role in his church. Commoners were divided into many groups

including honorable citizens, urban commoners, merchants, philistines, and

burghers. A special soslovie was the military.

Cossacks and other military men held their own sosloviia.

The peasant class

was the largest class of all and included numerous different ranks. Peasants were different from other classes in

that they were subject to both a poll tax (Подушный

оклад) and military conscription whereas members of other classes may not

have been. Single homesteaders, farmers,

monastic farmers, free agriculturalists, state peasants, landowners’ peasants,

appanage peasants, and ascribed peasants were all different classes among the

peasantry (Крестьяне). Some German settlers were categorized as free agriculturalists (Вольные хлебопашцы), while others

identified themselves as Крестьянин, a

variation on the Russian for peasant.

Each soslovie had different rights and

obligations; some were subject to certain kinds of taxation, some were subject

to military conscription, some were required to belong to guilds, each was

required to hold different types of passports, etc. Some classifications were allowed to travel

freely while others were restricted.

Some groups were able to engage in commerce, although limitations may

exist upon the characteristics of such.

Some groups were entitled to a certain degree of mobility and might

change classification depending upon employment tenure, net wealth or marriage

status. Members of a soslovie might petition the tsar to

modify their rights or privileges. Thus,

two sosloviia that may have been otherwise

almost identical may have been subject to dissimiliar entitlements or

restrictions.

Most European

countries similarly classified their populations and this system provided their

populace with social identity and clearly defined the peoples’ role within

society. One’s social status not only

determined how he paid taxes or became employed, but it also affected his day

to day life with very tangible measures.

A member of a peasant class would need to address higher class folks

with a certain title and they may need to give way in traffic or don their cap

when approached. Certain classes would

not have been able to legally possess arms of any sort, or achieve master

status within their vocation, or would need to quit their education after achieving

a certain level. From the American

standpoint, this system seems very restrictive and even inhumane, but these

systems existed in European societies for centuries.

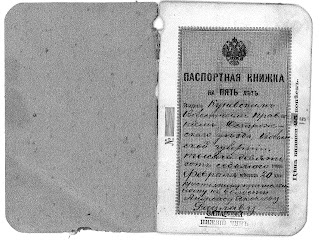

In his Russian

passport (pasportnaya kniga), Andreas

Ratzlaff identified Крестьянин as the soslovie to which he belonged.

-http://www.gla.ac.uk/0t4/crcees/files/summerschool/readings/Cadiot_2005_SearchingForNationality.pdf

-Across the

Revolutionary Divide: Russia and the USSR 1861-1945, Theodore R Weeks, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. Chapter 2

Tuesday, January 15, 2013

Metrical Books and Passports in 19th Century Russia

In 19th

Century Russia, citizens were recorded for a variety of purposes. Certifying identity provided the government with

citizenship records providing data to tabulate taxes, to provide lists for

military conscription, to record social estate status, to record land

ownership, or to preserve hereditary information. Citizenship records were kept in two ways: 1)

metrical books recorded by the clergy, and 2) internal passports purchased by

the citizen from the local police.

Metrical Books (Metrika) first appeared under Peter the

Great as a tool for cataloging the population of the Russian Empire. Beginning in the early 1700s, the government

required that clergy keep the metrical books, starting with the Russian

Orthodox Christians. Gradually, the

requirement spread to other religions in the Empire including Protestant

Christian, Roman Catholic, Islam and Judaism.

However, Buddhists in the east and the recognized pagans in European

Russia, escaped registration in metrical books entirely. The books created the fundamental register of

identity in the Empire and served as the basis for civil status. Regardless of social station or religion,

citizens were required to report to clergy to have recorded births, marriages

and deaths. The records created the

official documentation needed to identify birthdates, social and civil rights

of an individual, and provided lists from which were drawn tax registers and

military draft notices.

The government

issued instructions to clergy that metrical books were serious records and

their maintenance was of utmost importance.

Yearly, parish clergy submitted their metrical records to local

government authorities. This inclusion

of the clergy into such vital record-keeping shows that the Empire’s government

was indeed moored to religious foundations.

However, suspicions arose from time to time that certain clergy were not

fastidious enough in their record keeping which the government may have

evaluated as sabotage or treason.

Catholics, Jews and Muslims were from time to time put down as being

poor record keepers. Obviously there

were many problems with this system; Lutherans wanted to keep their records in

German, and Tatar Muslims in their native languages, etc. What was to be done if a citizen converted to

a different religion or confessed to no religion at all? What if a new religion was formed? Metrical books lasted until the Tsarist

government was put down by the Bolsheviks and the process was never taken over

by civic authorities.

-“Between

Particularism and Universalism: Metrical Books and Civil Status in the Russian

Empire, 1800-1914”, Paul W. Werth, UNLV.

Passports (pasportnaya kniga): internal passports

had been in place in Russia since the early 18th Century as Peter

the Great instituted their use as a way to certify a person’s legal place of

residence. Internal passports,

identifying the bearer by occupation, residence, and estate, helped regulate

travel and prevented evasion of taxes and military conscription. Passports held by those belonging to lower

social orders were registered by the local administrative institutions or rural

societies and bound the holder to his residence and form of employment; the

passport illustrated that a person belonged in a particular place and to a

particular vocation. By the late 19th

Century, members of lower social orders received passports that were valid for

five years, after which time the bearer was required to renew the document. Each social estate had its own local

administrative body. All members of

lower social estates were held responsible for the collective burden of taxes

levied on their social estate. The

administrative body certified that an individual had paid his taxes and was

eligible for a passport. Yearly fees were

also paid on the passport as a sort of tax on free movement. Local administrative bodies could also place

limitations on a person’s free travel rights.

Literate passport holders, usually members of higher estates, signed

their document while the lower orders made their mark or recorded their

physical description. Members of higher

estates received passports which were less restrictive.

-Documenting

Individual Identity, Jane

Caplan and John Torpey ed, Princeton 2001.

Chapter 4, pp 67-80.

Andreas Ratzlaff’s

passport is an example of a pasportnaya

kniga.

Tuesday, January 8, 2013

19th Century Volhynian administration

After being totally absorbed by the Russian Empire as a

result of the 3 Partitions of Poland during the late 18th Century,

Volhynia (Volyn Guberniya - Волинська

Губернія) was divided into counties (powiati

- повітів or okruga - округов) by the

Tsar’s government. Each powiat (повіт) had an administrative

center or county town (Губернскаго городовъ or Повітовий центр) which was

the namesake for the powiat. Immediately after the establishment of the

province within the Russian government, the Volhynian capital was Zaslaw

(Iziaslav). It was soon moved to

Novograd Volyn, and soon moved again to Zhytomyr, where it remained for the

duration of the 19th Century.

This map (from Wikipedia) shows the 12 Volhynian Powiati during the 19th Century, listed alphabetically according to the Russian alphabet. Ostrog Powiat is number 10:

This accompanying chart shows some statistical data for the 12 Volhynian Powiati, c.1897:

Each powiat was

divided into parishes or townships (volosti

- волостей). Powiati had between 16 and 25 volosti. Each volost

(волость) had its administrative center located in an important village and

each parish took its name from this village.

The Mennonite villages of Karlswalde, Antonovka, Leeleva and the rest,

fell administratively into Ostrog Powiat (Powiat Ostrozhsky – Острозький Повіт).

Antonovka was in Kunivska Volost

(Волость Кунівська) with its center at Kuniv, and Leeleva was in Pluzhanska Volost (Волость Плужанська)

with its center at Pluzhno.

This chart shows some further information regarding Powiat Ostrozhsky, c.1897:

Information is taken from the 1897 Russian census:

and the 1890 edition of the Brokgauz and Efron Encyclopedic

Dictionary

Monday, January 7, 2013

Volhynian Railway Service

Railways began to be established in Russia in the

19th Century and the rail line was built through Volhynia in the

1870s. By the early 1890s, the Ukrainian

Kiev-Brest line formed the main line through Volhynia, running roughly

northwest-southeast, serving Volhynian towns in between Kovel to

Berdichev (Berdichev was part of Volhynia until 1855, after which point it was moved into the Kiev Province for administrative purposes). A spur ran from Zdolbunov

(just south of Rovno) to Radziwill (Radziwilow). The Russians established the railway lines

with little regard for local municipalities; lines primarily led to Russian

cities or destinations and bypassed many important Ukrainian locations. For instance, of the 12 Volhynian cities that

were administrative centers for the 12 Volhynian counties, only one (Kovel) was directly served by the railway.

Furthermore, no direct railway link led between Kiev and Odessa, the two

most important Ukrainian cities (no direct highway link existed either!). From Ostrog, a person would have needed to

travel to Krivin, Wilbowno, Ozenin or Zdolbunov to catch a train.

This map shows the route in 1882. East from Kiev, a person could continue

travelling to Kursk, where connections could lead either to Kharkov or

Moscow. West from Kovel led to Lublin

(Poland) or Brest, in the province of Grodno.

A connection at Brest could also take a person to Moscow. Brest, along with Lemberg (L’vov) in Austrian

Galicia, were the two most important rail hubs near the western Ukrainian

frontier.

From an 1891 Volhynian calendar/almanac published by a company in Zhytomyr, we find

the local railway table. Prices are

given in rubles/kopecks and distances are given in versts (1 verst was about

the equivalent of 2/3rds of a mile).

With the current information, I don't know the railway schedule for this line. A similar publication (Volhynian calendar/almanac) published in 1906 indicates that there were 6 trains per day passing between Zhytomyr and Berdichev in that year. Zhytomyr and Berdichev were easily the largest cities in the area in the early years of the 20th Century, so it makes sense that train traffic would be busy between those locations. Out in the countryside trains probably didn't pass with as much frequency, but rail travel was the fastest, most efficient way to travel over land in those days.

Wednesday, January 2, 2013

Andreas and Susanna (Wedel) Ratzlaff photo

This is a photo of Andreas and Susanna (Wedel) Ratzlaff, taken in Lehigh, KS, in 1922 when Andreas was 53 and Susanna was 49. I'm unsure of the history of the photo, but it may have been taken by my grandfather, Albert Ratzlaff.

Thursday, November 29, 2012

Ostrog City and County Statistical Data, 1895

I recently came across some very interesting statistical information for the City and County of Ostrog, Volhynia Province, Russia, from the year 1895. The information is from the Brokgauza and Efrona Russian Encyclopedic Dictionary,

St. Petersburg/Leipzig, which was published several times between 1890 and the 1930s, in multiple volumes. This data is from the 1907 edition of the Encyclopedia, listing data from the year 1895 and can be found in its original form here. Keep in mind that this data separates Ostrog City from Ostrog County. City data is not included in County data.

|

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)